By Teresa Fang, Stentorian Editor-in-Chief

The name “eating disorders” (EDs) may seem straightforward, but they are one of the most misunderstood conditions. The rise of attractive, accessible social media has exposed mass populations to messages conflating the ideas of body image and health. EDs impact a broad spectrum of the population and for many different reasons and ways, making recovery complex; 1 in 11 Americans—or 28.8 million people—will develop an ED in their lifetime. For young people, 13 percent of adolescents will develop an ED by the age of 20.

Today, a general distrust of mainstream media outlets has led the public to flock to other reliable sources, leading medical sites to skyrocket in popularity and engagement. Modern readers are obsessed with personal image, and sites have adjusted and seen a drastic rise in health facts and biomedical communication. The seriousness of possible actions and repercussions has pushed objective data-driven information to subjective opinion-based suggestions, vulnerable to dishonest and dangerous arrangements to lead to misinformation, fearmongering, and competition. Thus, it is paramount that the general public becomes aware of the avenues of language a science communication piece possesses over their subjects and readers, especially with a topic so universal and nuanced yet often overlooked as eating disorders.

Language by the writer

To have a context for the ethical intricacy of biomedical communication when it comes to EDs, we must first look at the basic information available to the general public on the Internet. A quick Google of one of the most prevalent eating disorders, anorexia (even so, “anorexia” is an umbrella term for other EDs), will take us to the first search result by Mayo Clinic.

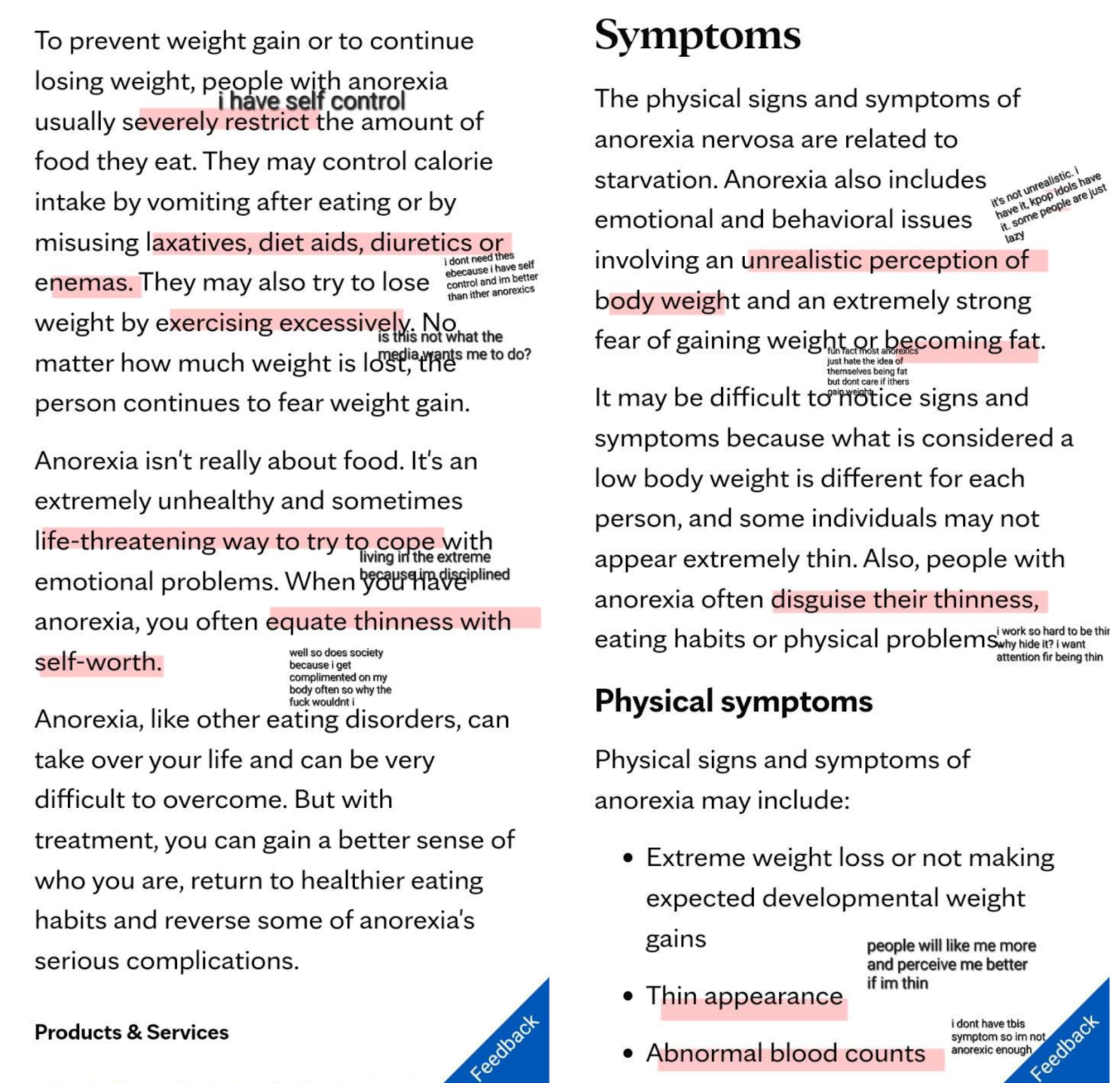

Like many informational websites, this article starts with an overview of the subject but its language regresses on the verge of being a piece of scientific writing versus giving directions as if it is the widely-accepted truth. A growing subjective language used to describe anorexia, which still is a widely-debated topic to be categorized medically, effectively freezes the process of teaching anorexia to telling readers how to see anorexics, disqualifying the root issue as how to deal with the aftermath rather than deal with how anorexia is borne in the minds of anorexics in the first place. The writers of Mayo Clinic unconsciously adopt this false essentialization of all anorexics as people who have no self-control, have unrealistic perceptions of life, have fatphobia, and starve themselves for personal validation of their self-worth.

This is not to casually accuse Mayo Clinic of scientific misrepresentation. They are among the world’s largest and most influential medical nonprofits, rated as the No. 1 hospital in the world for the past six years in the global hospital rating. In the organization’s mission and values statement, Mayo Clinic claimed that its vision is “transforming medicine to connect and cure as the global authority in the care of serious or complex disease” (Mayo Clinic); they view success as the paradigm of scientific progress and social compassion, a representation of their patients by collaboration so close to their patients the doctors can be called patients themselves.

Interpretations by the reader

As seen in Figure 1, a person with anorexia may interpret the language as hypocritical or as further justification to continue their starvation behaviors to be “better” or thinner than other anorexics for more societal attention and praise. With this article and that of other biomedical communication writers from organizations such as the National Eating Disorders Association and Healthline, the lines between objectiveness and subjectiveness are easily blurred.

At the same time, these texts gain traction on the Internet because of their authority and wide acceptance. Articles by lesser-known professionals and experts are often buried underneath higher-standing ethos, albeit they may provide the same information about eating disorders but at a level easier to digest and understand for both general audiences and people with EDs, like citizen science.

In a 2022 blog post on Octave, a mental health care provider-based company, author TJ Mocci explains why EDs are difficult to understand, along with suggestions on how to support people struggling with an ED. The ethos of the writer as a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (LMFT) and the logos of the broad but niche language become a powerfully visceral tool for the blog in promoting understanding in a non-triggering way; the use of targetted facts and statistics are reminiscent of active listening strategies that make an effort to understand what the other person is trying to communicate, making them feel less alone.

In regards to research articles that describe the latest updates/breakthroughs in producing medical cures for EDs, many articles are sourced from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision, which places the majority of the symptoms of each ED on physical symptoms, remaining vague in its behavioral ones, to categorize patients. Mocci utilizes careful wording, like pronouns, and lists “common signs,” not “symptoms,” of an eating disorder to inform readers how to be good allies/supporters. These are mostly behavioral, which is less emotionally/psychologically triggering and less likely to appeal as a fairy tale weight loss story. Intentional language can address readers directly and allows for a reader with an ED to gain sympathy for third parties, who may or may not also have EDs, which in turn allows them to gain sympathy for themselves.

Misinterpretations

As with any piece of writing, it is impossible to avoid misinterpretations, but the writer must be especially careful when consciously choosing language and interpretation to teach science because their work is dependent upon honesty. Some articles can fulfill both obligations; Mocci’s Octave blog can both inform and generate sympathy. This article promotes a pragmatic way for individuals, families, and communities to help people with EDs recover fundamentally. Other articles may disregard language and interpretation to get their information across. The growing demand to get immediate answers at its extremes has altered people’s perceptions of honesty. Technology has superseded honesty to dangerous trust. Now, more than ever, biomedical communication must be aware of the nature of this ethic.

Leave a Reply